Book Reviews

There are few books that I would give a score of 10/10. This must be reserved for the classics: Don Quixote, War and Peace, The Brothers Karamazov, many of the novels of Charles Dickens etc. (and, in deference to my wife, probably the novels of Jane Austen as well). Perfect tens describe works of such scope and scale that, as a writer, I am left thinking--why bother? No one else can write like this. No one else could have such depth of understanding of the human condition. And, as a reader, works in which I am completely transported, engaged, won over--no other universes seem possible.

I hold out one more condition in my judging of novels: that they should be "uplifting", that they should, if only temporarily, make me a better person after reading them. No matter how skillful a writer may be, if he does not create for me one admirable or sympathetic character within the first fifty pages or so, I throw my hands up in despair and put down the book.

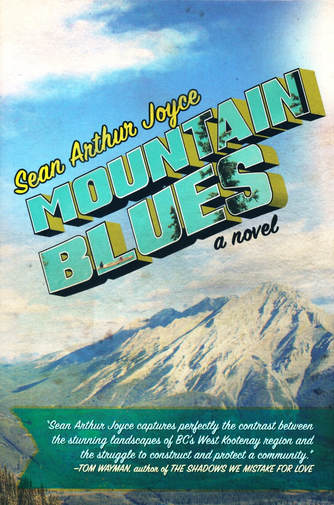

Mountain Blues

by Sean Arthur Joyce

In Mountain Blues, author Sean Arthur Joyce, takes the reader on an intimate journey through the fictional Glacier Valley, and the tiny mountain towns which hug the shores of Sapphire and Sturgeon Lake.

While the Kootenay scenery is remarkable and lovingly depicted, what makes Mountain Blues so memorable are the many colourful characters which inhabit the book. There are the loggers, the new-agers, the aging hippies, and Roy Breen himself (the novel’s narrator, an escapee journalist from Vancouver). The interpersonal relationships between these groups is highly dynamic, and emotions frequently run high when characters meet face-to-face.

Prominent among the cast of eccentrics is Moss, the rastafarian Jamaican expat, Moonglow, the flower child, Marie-Louise, the heavy-smoking Metis and Bill Radford, the “local contrarian”.

Those who are not obviously eccentric tend to be highly political and often the border between these two states is blurred.

Most of the action in the novel takes place in and around the tiny town of El Dorado (population 796). But, as Roy Breen says, this is no “proto-Appalachian village.” Its citizens are well-versed in the tactics of protest and peaceful disobedience. When their hospital is threatened with reduced hours, they mobilize quickly and creatively and become a major headache for the bureaucrats back in Victoria.

Joyce is not afraid to tackle serious issues such as truth and fiction in the media, the perils of materialism, the efficacy of political protest, and the mistreatment of First Nations. Yet, even while dealing with these serious topics, Joyce cannot hide the love he has for his characters. He loves not just their strengths but their flaws, their best intentions, their sweet humanity.

While the Kootenay scenery is remarkable and lovingly depicted, what makes Mountain Blues so memorable are the many colourful characters which inhabit the book. There are the loggers, the new-agers, the aging hippies, and Roy Breen himself (the novel’s narrator, an escapee journalist from Vancouver). The interpersonal relationships between these groups is highly dynamic, and emotions frequently run high when characters meet face-to-face.

Prominent among the cast of eccentrics is Moss, the rastafarian Jamaican expat, Moonglow, the flower child, Marie-Louise, the heavy-smoking Metis and Bill Radford, the “local contrarian”.

Those who are not obviously eccentric tend to be highly political and often the border between these two states is blurred.

Most of the action in the novel takes place in and around the tiny town of El Dorado (population 796). But, as Roy Breen says, this is no “proto-Appalachian village.” Its citizens are well-versed in the tactics of protest and peaceful disobedience. When their hospital is threatened with reduced hours, they mobilize quickly and creatively and become a major headache for the bureaucrats back in Victoria.

Joyce is not afraid to tackle serious issues such as truth and fiction in the media, the perils of materialism, the efficacy of political protest, and the mistreatment of First Nations. Yet, even while dealing with these serious topics, Joyce cannot hide the love he has for his characters. He loves not just their strengths but their flaws, their best intentions, their sweet humanity.

Almost as much, he loves the place where they live, and truly it is a special place. El Dorado lives up to its name if one thinks of gold in a metaphorical sense. The lifestyle of the valley is golden. It is a hidden Shangri-la among the mountains. It echoes strongly of the town of Cicely from the television series Northern Exposure whose eloquent and earthy characters inhabited a special place in the imaginations of many throughout the Nineties.

But here’s the kicker: El Dorado has one great advantage over Cicely; it’s a real place. Read Joyce’s book first, then go find it.

It's published by NuWest Press.

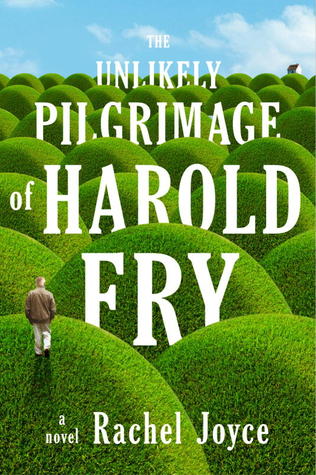

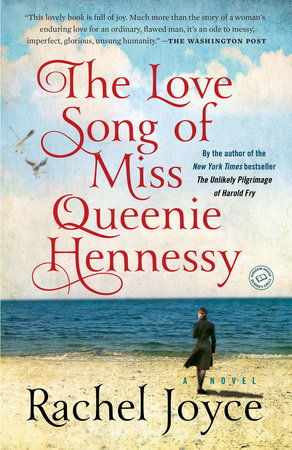

The Love Song of Miss Queenie Hennessy

& The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry

by Rachel Joyce

Rachel Joyce’s The Love Song of Miss Queenie Hennessy is a beautiful book and a companion piece to the The Unlikely Pilgrimmage of Harold Fry. Joyce writes with an impressive economy of words, yet surprises the reader regularly with bursts of poetry as sweet as the best of impressionist paintings. However, what I most admire about Joyce’s writing is the connection she makes with the human heart.

Perhaps this connection can be attributed Joyce’s long and distinguished theatre career where, in her many varied roles, she has had to explore the subtle workings of human personality and motive. Perhaps her experience in writing BBC radio dramas has also specially equipped her to write authentic and poignant dialogue. Whatever the reason, Joyce employs all the right tools to take the reader on an intimate journey with her protagonists.

In the first of Joyce’s books, her protagonist is the unlikely Harold Fry, among the most introverted of men; he works in a brewery; there is nothing at all remarkable about him. Then he receives a letter from Miss Queenie Hennessey, a woman who used to work with him. It’s a short letter: a greeting and a goodbye. She shares the news that she is dying but, with typical English politeness, simply wants to thank him for the time they spent together.

Harold mulls over the implications of this letter. Then, seemingly out of the blue, without taking into consideration at all the practical difficulties involved, decides he will go and visit Queenie. He decides, in fact, that he will walk there. In spite of the fact that he lives in the south of England and she at the extreme northeast corner of the country.

We follow Harold on his journey. We share the pain of his blisters, enjoy with him the feel of dew on the grass as he wakes to a rising sun. His very private affair gradually becomes more public as the media learn about this strange little man and his “unlikely pilgrimage”. Indeed, for me, this is the most moving part of Harold’s story—how his very personal pilgrimage is co-opted by all manner of strangers who choose to join him on his walk (one even dressed in a gorilla costume of all things). At this point I know I would have called off the whole enterprise, but not Harold. Harold feels an obligation to honour the motives of his fellow walkers, no matter what they may be, and feels he has no right to tell them what to do. Such an attitude, I think, almost qualifies him for sainthood. And still he walks, not knowing what to expect next, with no knowledge of where he will end up that day or where he will sleep. On his way, he sends postcards to Queenie, telling her how far he has walked, and urging her to “hang on” till he gets there.

For the entire book, Queenie Hennessy is hardly more than a name or an idea, the medieval lady for whom the knight has made a pledge, but in the second book, Queenie’s story takes centre stage.

In The Love Song of Miss Queenie Hennessy we find Queenie lying in in a hospice bed tended by nuns. Her cancer is very advanced. Her face is grotesquely disfigured and she has difficulty eating. Nevertheless she is determined to write a letter to Harold. It is more a confession than a letter. She has so much she needs to explain to Harold before he arrives. We meet other colourful personalities at the Hospice, all of them dying, all of them “hanging on” if for no other reason than to see if Harold Fry will actually come.

Most memorable among the hospice’s characters are the nuns themselves, especially one Sister Inconnue who helps Queenie write her letter. Queenie’s life has much sadness and regret in it but, in reviewing it, she finds unexpected joy too. With great skill and tenderness, Joyce allows us to follow Queenie in her exploration of the meaning and depths of love.

These are wonderful books, and a great antidote for the despair and ennui which fills so much of modern literature. Joyce introduces us to characters who, though humble in circumstance, have great depth of heart. I highly recommend these books.

9/10

SIDEWAYS: Memoir of a Misfit

by Diana Morita Cole

I am hard-pressed to find a better summary of Cole’s memoir than the one which appears on the book’s jacket: “Lying sideways in her mother’s womb, Diana overhears the Minidoka prison doctor speculate that her 44-year-old mother may not survive childbirth. In response, Diana flips over in utero, thereby saving her mother’s life. Her genius to survive obstacles and dire outcomes is what makes Sideways: Memoir of a Misfit an intriguing tale of fresh twists and ironic triumphs.”

How wonderful for the author to begin her book with a reflection in utero! She describes her flip as “one of my rare moments of grace,” but does herself an injustice here. The reader finds many moments of grace as Diana navigates through the extremely complex inter-relationships existing between herself, her siblings, and her parents. As the youngest of nine this navigation would be challenging enough, but is made even more so by the cultural divide that cuts through her family like a geologic fault line.

In a memoir one does not necessarily expect poetry, but some of Cole’s childhood recollections are written with such poignancy they could easily be described as such. I was especially moved by her loving description of sharing a hot bath with her mother. “Her stomach stood out like a mountain,” Cole writes, “a living monument to the nine of us that had started life deep within its mystery. I would try to push it down with my small hand, but it shot back up refusing to obey...”

Cole has done a great service in educating people like me—woefully ignorant for the most part—of the injustice and hardships suffered by Japanese internees and their families during and after the Second World War. Courageously, with exquisite detail, and often with humour, Cole tells us what it was like to grow up in Chicago at this pivotal time in history, in this particular family.

Cole includes a postscript at the end of her book in which she relates her experience as an American internee to the experience of internees in Canada. Referring back to fellow internee, Canadian poet, Roy Miki, she says, “We grew up in shadows of yearning, dark corridors trod by kin who were compelled by longing to suffuse hollow places with meaning and psalm.” Here is one more case of poetry—quite wonderfully—asserting itself into the work!

Sideways: Memoir of a Misfit both educates and inspires. What more could one ask for?

How wonderful for the author to begin her book with a reflection in utero! She describes her flip as “one of my rare moments of grace,” but does herself an injustice here. The reader finds many moments of grace as Diana navigates through the extremely complex inter-relationships existing between herself, her siblings, and her parents. As the youngest of nine this navigation would be challenging enough, but is made even more so by the cultural divide that cuts through her family like a geologic fault line.

In a memoir one does not necessarily expect poetry, but some of Cole’s childhood recollections are written with such poignancy they could easily be described as such. I was especially moved by her loving description of sharing a hot bath with her mother. “Her stomach stood out like a mountain,” Cole writes, “a living monument to the nine of us that had started life deep within its mystery. I would try to push it down with my small hand, but it shot back up refusing to obey...”

Cole has done a great service in educating people like me—woefully ignorant for the most part—of the injustice and hardships suffered by Japanese internees and their families during and after the Second World War. Courageously, with exquisite detail, and often with humour, Cole tells us what it was like to grow up in Chicago at this pivotal time in history, in this particular family.

Cole includes a postscript at the end of her book in which she relates her experience as an American internee to the experience of internees in Canada. Referring back to fellow internee, Canadian poet, Roy Miki, she says, “We grew up in shadows of yearning, dark corridors trod by kin who were compelled by longing to suffuse hollow places with meaning and psalm.” Here is one more case of poetry—quite wonderfully—asserting itself into the work!

Sideways: Memoir of a Misfit both educates and inspires. What more could one ask for?

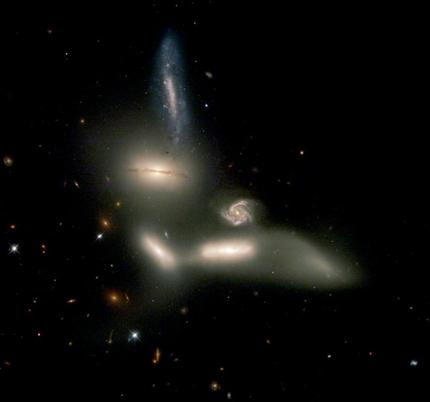

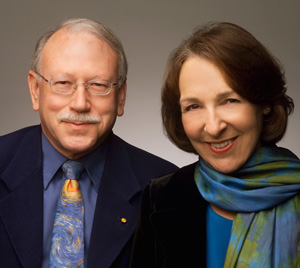

View from the Center of the Universe

by Joel R. Primack & Nancy Ellen Abrams

This book by Joel Primack, physics professor, and his wife Nancy Abrams, is the most important book I have read in the last decade, maybe the last several decades. Last month I finished reading it for the fourth time, this time liberally marking up the text with yellow highlighter.

In this work, Primack and Abrams attempt a remarkable thing: to synthesize all our current understanding of cosmology into a new world culture myth about the universe and humankind's place in it.

The authors do not use the word 'myth' in the sense of Santa Claus or the Easter Bunny or something that is patently juvenile and untrue. Myth is at the heart of human spirituality. Myth is the story we make for ourselves that explains our relationship to the universe.

All the world's great civilizations have had great myths whose principle purpose was to explain existence and give purpose to each person's life. Our modern age is without such a myth--we are perhaps suspicious of myths and think ourselves too sophisticated to need them. But the lack of such a unifying (and yes 'reassuring') myth goes a large way in explaining our modern angst.

In this work, Primack and Abrams attempt a remarkable thing: to synthesize all our current understanding of cosmology into a new world culture myth about the universe and humankind's place in it.

The authors do not use the word 'myth' in the sense of Santa Claus or the Easter Bunny or something that is patently juvenile and untrue. Myth is at the heart of human spirituality. Myth is the story we make for ourselves that explains our relationship to the universe.

All the world's great civilizations have had great myths whose principle purpose was to explain existence and give purpose to each person's life. Our modern age is without such a myth--we are perhaps suspicious of myths and think ourselves too sophisticated to need them. But the lack of such a unifying (and yes 'reassuring') myth goes a large way in explaining our modern angst.

Most of us, in some cases on an unconscious level, think of the universe as a vast, empty expanse, and regard our own personal existence to be without meaning or significance.

The View from the Center of the Universe argues that this lonely, existential view is based on an outdated cosmology, that it is does not at all reflect a vision of the universe as it 'actually is'.

The universe as it 'actually' is, filled with virtual particles popping in and out of existence, filled with dark matter that we can't even see, and with the very fabric of space expanding exponentially, is a strange and wondrous place.

What is even more strange and wondrous is that mankind seems to have a central and pivotal place in all this. What an exciting idea! And how brilliantly the authors expound it.

The View from the Center of the Universe argues that this lonely, existential view is based on an outdated cosmology, that it is does not at all reflect a vision of the universe as it 'actually is'.

The universe as it 'actually' is, filled with virtual particles popping in and out of existence, filled with dark matter that we can't even see, and with the very fabric of space expanding exponentially, is a strange and wondrous place.

What is even more strange and wondrous is that mankind seems to have a central and pivotal place in all this. What an exciting idea! And how brilliantly the authors expound it.

10/10

Interesting to note that this book goes a long way to addressing the problem with modern civilization as described by Kenneth Clark at the end of his book (see below). Clark said, “the trouble is that there is still no centre. The moral and intellectual failure of Marxism has left us with no alternative to heroic materialism [capitalism], and that isn’t enough.”

It could just be that Primack and Abrams have shown us a way forward.

Civilisation

by Kenneth Clark

“At this point I reveal myself in my true colours, as a stick-in-the-mud. I hold a number of beliefs that have been repudiated by the liveliest intellects of our time. I believe that order is better than chaos, creation better than destruction. I prefer gentleness to violence, forgiveness to vendetta. On the whole I think that knowledge is preferable to ignorance, and I am sure that human sympathy is more valuable than ideology. I believe that in spite of the recent triumphs of science, men haven’t changed much in the last two thousand years; and in consequence we must still try to learn from history. History is ourselves. I also hold one or two beliefs that are more difficult to put shortly. For example, I believe in courtesy, the ritual by which we avoid hurting other people’s feelings by satisfying our own egos. And I think we should remember that we are part of a great whole, which for convenience we call nature. All living things are our brothers and sisters. Above all, I believe in the God-given genius of certain individuals, and I value a society that makes their existence possible.”

These are not my words—though I wish they were—since they so well echo my own ‘quaint’ ‘old-fashioned’ thinking. They were written by Kenneth Clark, British art historian, near the end of his book Civilisation, first printed in 1969.

The book—which was based on the seminal TV series of the same name—was given to me by my dear friends, Henry Kutzko and Jaan Reitav on the occasion of my 21st birthday. Reading it again forty years later, it is clear to me how influential this book has been in the formation of my artistic tastes and my historical perspective.

And how delightful all these years later to look at some of the illustrations of paintings, sculpture and architecture and say to myself, “yes! I’ve seen that! It truly is magnificent!”

I did not pursue a study in history at university, other than auditing a course of ancient Greek history at one point. But always stories of the past have nagged at me. They have made up the bulk of my material in my writing, both my dramas and my fiction and, more often than not, I have paid almost obsessive attention to great ‘individuals’ of the past, both mythic and historical.

Like Kenneth Clark, at some fundamental level, I seem to believe in the transcendent power of “genius”.

The book—which was based on the seminal TV series of the same name—was given to me by my dear friends, Henry Kutzko and Jaan Reitav on the occasion of my 21st birthday. Reading it again forty years later, it is clear to me how influential this book has been in the formation of my artistic tastes and my historical perspective.

And how delightful all these years later to look at some of the illustrations of paintings, sculpture and architecture and say to myself, “yes! I’ve seen that! It truly is magnificent!”

I did not pursue a study in history at university, other than auditing a course of ancient Greek history at one point. But always stories of the past have nagged at me. They have made up the bulk of my material in my writing, both my dramas and my fiction and, more often than not, I have paid almost obsessive attention to great ‘individuals’ of the past, both mythic and historical.

Like Kenneth Clark, at some fundamental level, I seem to believe in the transcendent power of “genius”.

If, by some chance, you’ve never seen the television series or read the book (which like most books is better and deeper than its visual counterpart), I highly recommend both. Clark gives the viewer/reader a sweeping look at European ‘civilisation’; he tries to define it, explain it, and gives us an almost heart-rending appreciation of its fragility.

A fascinating and inspiring read, even after a break of forty years...

10/10

Clark ends his book with a quote from W.B. Yeats which although written almost century before still sounds startlingly current:

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Clark goes on to say, “the trouble is that there is still no centre.” In the forty plus years since Clark wrote this, I fear very little has changed. “The moral and intellectual failure of Marxism has left us with no alternative to heroic materialism [capitalism], and that isn’t enough.”

In the meantime, plant a tree, hug a friend, and make some art!

In the meantime, plant a tree, hug a friend, and make some art!

Magnificence

by Lydia Millet

Magnificence is not magnificent. I say this after reading through half the novel. I can go no further. I do not make this judgement lightly, especially upon an author whom, not long ago, I professed to be my favourite new writer.

In Magnificence, Millet continues to follow the fortunes of characters introduced two books ago. In How the Dead Dream we first meet ‘T’, and unlikely capitalist hero, who ends up being lost in the jungles of Belize. In the second book, Ghost Lights, we follow the fortunes of Hal who goes out to look for him.

Finally, in Magnificence, in great psychological detail, we delve into the life of Susan, Hal’s husband. Susan blames herself for her husband’s death. Logically the blame is indirect, at best. Nevertheless, again and again she refers to herself as a murderer, to the point where, as a reader, I cannot help declaring “the lady doth protest too much.” I do not like Susan and do not sympathize with her angst. I like her boss, T, much more, but he has only a small role to play in Magnificence. I like Susan’s daughter, Casey, but again, she is a minor character.

The great plot-changer in the first half of Magnificence comes when Susan inherits a great stately home in Pasadena. Its scores of rooms are adorned with the heads of wild animals from all over the world. Susan is both haunted and entranced by these heads. They seem to have deep symbolic meaning for her. But after 136 pages, I have to ask myself, what has really HAPPENED in the book?

Reluctantly, I have to say that, for me at least, this is a BORING book.

Of course, I have only read half of it. Maybe breath-taking revelations are just around the corner. Maybe the pace picks up mightily. But honestly, Lydia Millet, how patient do you expect your readers to be?

With Magnificence I hope Millet has at least put an end to this trilogy. The first book was wonderful, the second, pretty good. But now it’s time to move on to new material.

In Magnificence, Millet continues to follow the fortunes of characters introduced two books ago. In How the Dead Dream we first meet ‘T’, and unlikely capitalist hero, who ends up being lost in the jungles of Belize. In the second book, Ghost Lights, we follow the fortunes of Hal who goes out to look for him.

Finally, in Magnificence, in great psychological detail, we delve into the life of Susan, Hal’s husband. Susan blames herself for her husband’s death. Logically the blame is indirect, at best. Nevertheless, again and again she refers to herself as a murderer, to the point where, as a reader, I cannot help declaring “the lady doth protest too much.” I do not like Susan and do not sympathize with her angst. I like her boss, T, much more, but he has only a small role to play in Magnificence. I like Susan’s daughter, Casey, but again, she is a minor character.

The great plot-changer in the first half of Magnificence comes when Susan inherits a great stately home in Pasadena. Its scores of rooms are adorned with the heads of wild animals from all over the world. Susan is both haunted and entranced by these heads. They seem to have deep symbolic meaning for her. But after 136 pages, I have to ask myself, what has really HAPPENED in the book?

Reluctantly, I have to say that, for me at least, this is a BORING book.

Of course, I have only read half of it. Maybe breath-taking revelations are just around the corner. Maybe the pace picks up mightily. But honestly, Lydia Millet, how patient do you expect your readers to be?

With Magnificence I hope Millet has at least put an end to this trilogy. The first book was wonderful, the second, pretty good. But now it’s time to move on to new material.

The Glass Seed

by Eileen Delehanty Pearkes

Pearkes has written a remarkable book. It is moving, lyrical, and always powerful. In it the author has shared her most intimate thoughts about life, death and love, set against the context of her mother’s losing battle with Alzheimer’s and her own search for meaning.

Dementia, in all its forms, is a devastating disease. It leads Pearkes to ask “Is it possible that Alzheimer’s disease has risen as an illness of our time because of something we need to learn? Relinquish the mind. Let go of the hollow husk of material being. Embrace a power beyond human accomplishment. Accept mortality. Then see what happens.”

I will forever remember the scenes Pearkes describes where she sits with her mother, a mother no longer resembling the woman she grew up with, who nurtured her, who was strong and in control, and who now can no longer even mutter an intelligent sentence, nor recognize her own daughter. And still Pearkes holds her, sings a nursery rhyme to her, loves the pre-verbal essence that is still her mother.

It is almost too deep a moment to comment on.

There is a stage in the illness when her mother still manages to speak in short sentences, though many seem nonsensical. On one occasion, Pearkes’s mother reminisces about her husband and says of him “Something was in there. In him. I wished he could get it out. It made him so unhappy.” Then, a moment later, she looks directly at her daughter and, in preternatural wisdom, blurts out, “You are like that too.”

This book challenges us with the question ‘are we more than the sum of our memories’? Clearly Pearkes thinks we are, and her exploration of that question is multifaceted and poignant. “The mind,” she concludes, “for all its potential cannot be depended on the way the heart can.”

I think of St. Exupery’s Little Prince perched on his asteroid, and of his fox and the snake which will help him make his final journey.

Goodnight sweet prince.

Dementia, in all its forms, is a devastating disease. It leads Pearkes to ask “Is it possible that Alzheimer’s disease has risen as an illness of our time because of something we need to learn? Relinquish the mind. Let go of the hollow husk of material being. Embrace a power beyond human accomplishment. Accept mortality. Then see what happens.”

I will forever remember the scenes Pearkes describes where she sits with her mother, a mother no longer resembling the woman she grew up with, who nurtured her, who was strong and in control, and who now can no longer even mutter an intelligent sentence, nor recognize her own daughter. And still Pearkes holds her, sings a nursery rhyme to her, loves the pre-verbal essence that is still her mother.

It is almost too deep a moment to comment on.

There is a stage in the illness when her mother still manages to speak in short sentences, though many seem nonsensical. On one occasion, Pearkes’s mother reminisces about her husband and says of him “Something was in there. In him. I wished he could get it out. It made him so unhappy.” Then, a moment later, she looks directly at her daughter and, in preternatural wisdom, blurts out, “You are like that too.”

This book challenges us with the question ‘are we more than the sum of our memories’? Clearly Pearkes thinks we are, and her exploration of that question is multifaceted and poignant. “The mind,” she concludes, “for all its potential cannot be depended on the way the heart can.”

I think of St. Exupery’s Little Prince perched on his asteroid, and of his fox and the snake which will help him make his final journey.

Goodnight sweet prince.

The Glass Seed is a book of sweet and sad wonders.

THE GEOGRAPHY OF MEMORY

By Eileen Delehanty Pearkes

Recovering Stories of a Landscape’s

First People

Some books have a narrow focus and this would be one. Its appeal is largely to people who presently live in, or have at least experienced, the magical landscape of the West Kootenays in the southeast corner of British Columbia.

Pearkes’s descriptions of the pre-European landscape are vivid, often poetic. She paints a picture of unspoiled forests, before mine sites had been established, and of untamed waters, yet to succumb to the constrictive work of dams. With equal vividness, and much love, she tells the tales of the people who first lived here, the Sinixt or Lakes people, focusing particularly on the lives of aboriginal women. She describes their way of life, their deep dependence on the land, and insists throughout the book how all of us, even 21st century white people, are inextricably tied to the landscape we live in.

Especially poignant to me are her recollections of walking over exposed river beds along the Arrow Lakes where the Sinixt had once flourished, and learning how, buried beneath the dark silt, arrowheads can still be found, but also to be reminded that this landscape can be walked upon only for a short time each year, bowing finally to the demands of dowstream dams. Or another time, her imagining the Pacific Salmon—the very lifeblood of the Sinixt people for centuries—jumping over the turbulent waters at Kettle Falls, on their way to their prehistoric spawning beds, except that now they no longer can. In place of the Falls there is now a mighty dam. And how the memory of catching leaping salmon has become no more than a fleeting memory for many of the Sinixt.

Pearkes does us a great service by “recovering” the stories of a people almost forgotten. After reading “The Geography of Memory,” it is as if the valleys I have walked in and mountains I have peered up at, for decades, have taken on an added dimension. Now I can “see” the people who lived here, who trod lightly, but significantly. Both they and I have scrambled across scree to look at the shaggy mountain goat, both collected the same huckleberries (‘sweet’ berries), have dove into the same water on a summer’s day thinking, ‘my God, that’s cold!’ each of us shaped, to different degrees, by the magical landscape surrounding us.

Pearkes’s book has helped connect me to a landscape and past I knew but dimly, and that is a great gift. Such a feat lifts the work beyond the narrow into something quite big.

First People

Some books have a narrow focus and this would be one. Its appeal is largely to people who presently live in, or have at least experienced, the magical landscape of the West Kootenays in the southeast corner of British Columbia.

Pearkes’s descriptions of the pre-European landscape are vivid, often poetic. She paints a picture of unspoiled forests, before mine sites had been established, and of untamed waters, yet to succumb to the constrictive work of dams. With equal vividness, and much love, she tells the tales of the people who first lived here, the Sinixt or Lakes people, focusing particularly on the lives of aboriginal women. She describes their way of life, their deep dependence on the land, and insists throughout the book how all of us, even 21st century white people, are inextricably tied to the landscape we live in.

Especially poignant to me are her recollections of walking over exposed river beds along the Arrow Lakes where the Sinixt had once flourished, and learning how, buried beneath the dark silt, arrowheads can still be found, but also to be reminded that this landscape can be walked upon only for a short time each year, bowing finally to the demands of dowstream dams. Or another time, her imagining the Pacific Salmon—the very lifeblood of the Sinixt people for centuries—jumping over the turbulent waters at Kettle Falls, on their way to their prehistoric spawning beds, except that now they no longer can. In place of the Falls there is now a mighty dam. And how the memory of catching leaping salmon has become no more than a fleeting memory for many of the Sinixt.

Pearkes does us a great service by “recovering” the stories of a people almost forgotten. After reading “The Geography of Memory,” it is as if the valleys I have walked in and mountains I have peered up at, for decades, have taken on an added dimension. Now I can “see” the people who lived here, who trod lightly, but significantly. Both they and I have scrambled across scree to look at the shaggy mountain goat, both collected the same huckleberries (‘sweet’ berries), have dove into the same water on a summer’s day thinking, ‘my God, that’s cold!’ each of us shaped, to different degrees, by the magical landscape surrounding us.

Pearkes’s book has helped connect me to a landscape and past I knew but dimly, and that is a great gift. Such a feat lifts the work beyond the narrow into something quite big.

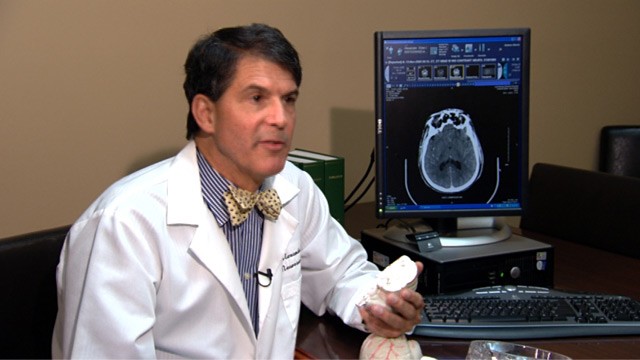

Proof of Heaven

A Neurosurgeon's Journey into the Afterlife

by Eben Alexander M.D.

There have been many books and accounts of people’s Near Death Experiences (NDEs) in recent years. What distinguishes this one is that is was written by a skeptic and a skeptic supremely qualified to speak about the workings of the human brain.

Alexander talks about how dismissive he had previously been of patients’ claims of e.g. walking down a long tunnel, of meeting dead family members and friends, and all the other claims so common to NDEs.

He had put down such claims to a deprivation of oxygen to the brain, or an abnormal jolt of hormones as body systems began to shut down and so forth, all pat explanations which he and his colleagues regularly provided when confronted with such accounts.

Everything changed, however, when Alexander himself experienced and NDE in 2008 as the result of a very rare attack of a bacterial meningitis which doctors fully expected would kill him. Alexander was put into a medically-induced coma. According to Alexander, the virulent e coli bacteria, which was attacking his neocortex at this time, completely shut down his higher brain functions. This process should have made any kind of hallucinations impossible. In fact, Alexander’s consciousness should have been completely disabled.

And yet Alexander had a very rich sensory experience during his week long coma. This is proof, Alexander argues, that consciousness exists independent of the brain and body.

Alexander talks about how dismissive he had previously been of patients’ claims of e.g. walking down a long tunnel, of meeting dead family members and friends, and all the other claims so common to NDEs.

He had put down such claims to a deprivation of oxygen to the brain, or an abnormal jolt of hormones as body systems began to shut down and so forth, all pat explanations which he and his colleagues regularly provided when confronted with such accounts.

Everything changed, however, when Alexander himself experienced and NDE in 2008 as the result of a very rare attack of a bacterial meningitis which doctors fully expected would kill him. Alexander was put into a medically-induced coma. According to Alexander, the virulent e coli bacteria, which was attacking his neocortex at this time, completely shut down his higher brain functions. This process should have made any kind of hallucinations impossible. In fact, Alexander’s consciousness should have been completely disabled.

And yet Alexander had a very rich sensory experience during his week long coma. This is proof, Alexander argues, that consciousness exists independent of the brain and body.

Some aspects of Alexander’s heavenly vision were common to most NDEs. Many were unique, including a long period where he seemed to have no awareness of himself as a separate individual. He seemed to have no memories of his Earthly life nor did he meet any figures he recognized.

Only a relatively small portion of the book is devoted to what Alexander experienced during his vision. But overwhelmingly he was left with the positive assurance that he was loved. That love was the key to everything in the universe. And that he could do no wrong.

Most of the book is devoted to describing Alexander’s illness in detail and the reactions of his family and friends while he was ill, and to an examination of the medical implications of what had happened.

I doubt this book will change the mind of a firm atheist who allows no possibility for an afterlife. For, as many have argued, it is impossible to change the mind of anyone based on sensory experience, for every sensory experience (even the sensation of being skeptical about sensory experiences) is open to question, and cannot be proved or disproved by logic.

Alexander’s account may, however, be a comfort to ‘believers’, providing another anecdotal report—and from a markedly unexpected source—that a loving God is ready to welcome them at the end of their Earthly lives.

It is worth noting that Proof of Heaven has come under attack by many of Alexander’s peers who claim the book is completely unscientific. Most take great issue with Alexander’s assertion that his neocortex had completely shut down during his illness. I, for one, am not qualified to choose between the opinions of competing neurosurgeons, but it seems only natural to me that there should be such a dispute.

All this being said, I did find this book an interesting read. It was written in a slow, clear style—clarity of presentation seeming to be uppermost in the mind of the author. The world is full of skeptics, I know, and some would claim Eben Alexander, M.D., had profit in mind when he published this book, but I find that hard to believe. With this publication Alexander opened himself up to ridicule on the highest level and professional shunning. All in a quest for fame? Wealth? It doesn’t wash for me. For me, this is the account of a sincere and “surprised” believer.

7/10

Only a relatively small portion of the book is devoted to what Alexander experienced during his vision. But overwhelmingly he was left with the positive assurance that he was loved. That love was the key to everything in the universe. And that he could do no wrong.

Most of the book is devoted to describing Alexander’s illness in detail and the reactions of his family and friends while he was ill, and to an examination of the medical implications of what had happened.

I doubt this book will change the mind of a firm atheist who allows no possibility for an afterlife. For, as many have argued, it is impossible to change the mind of anyone based on sensory experience, for every sensory experience (even the sensation of being skeptical about sensory experiences) is open to question, and cannot be proved or disproved by logic.

Alexander’s account may, however, be a comfort to ‘believers’, providing another anecdotal report—and from a markedly unexpected source—that a loving God is ready to welcome them at the end of their Earthly lives.

It is worth noting that Proof of Heaven has come under attack by many of Alexander’s peers who claim the book is completely unscientific. Most take great issue with Alexander’s assertion that his neocortex had completely shut down during his illness. I, for one, am not qualified to choose between the opinions of competing neurosurgeons, but it seems only natural to me that there should be such a dispute.

All this being said, I did find this book an interesting read. It was written in a slow, clear style—clarity of presentation seeming to be uppermost in the mind of the author. The world is full of skeptics, I know, and some would claim Eben Alexander, M.D., had profit in mind when he published this book, but I find that hard to believe. With this publication Alexander opened himself up to ridicule on the highest level and professional shunning. All in a quest for fame? Wealth? It doesn’t wash for me. For me, this is the account of a sincere and “surprised” believer.

7/10

Never GOING BACK

by Antonia Banyard

Three friends are driving from Vancouver to Nelson, BC, to commemorate the death of a friend. For me, this is a premise that would normally not raise excitement. But very soon I am swept up by the vivid characterizations of the story’s main characters: Siobhan, Lance and Evan. Banyard draws them in loving detail and makes the reader care for them deeply. Each of them, though adults, has unfinished business. Ten years before, their “rite of passage” was interrupted, and this trip to Nelson may be their last chance to sort things out. Lance, Evan and Siobhan—each of them is vulnerable and flawed, yet each just on the cusp of achieving a greater and more loving maturity.

Lance is my favourite character: in a state of emotional somnolence as the novel opens, wishing a UFO would land in his backyard and whisk him away. He is a dreamer, naïve, a procrastinator. He has the heart of a monk and an explorer all at once. Yet as the story unfolds, it is probably he who makes the greatest emotional journey.

Banyard has a wonderful grasp of emotional subtlety, paying careful attention to a small gesture or unspoken word. It is worth mentioning that two out of her three main characters are male, yet Banyard, effortlessly, it seems, writes in a cross-gender voice.

There is a gentle, seductive rhythm to this work, echoing perhaps the essence of the place she writes about. The writing is precise, yet poetic and, Banyard succeeds brilliantly in capturing the unique quality of the Kootenays and the people who live here.

An enchanting read.

Lance is my favourite character: in a state of emotional somnolence as the novel opens, wishing a UFO would land in his backyard and whisk him away. He is a dreamer, naïve, a procrastinator. He has the heart of a monk and an explorer all at once. Yet as the story unfolds, it is probably he who makes the greatest emotional journey.

Banyard has a wonderful grasp of emotional subtlety, paying careful attention to a small gesture or unspoken word. It is worth mentioning that two out of her three main characters are male, yet Banyard, effortlessly, it seems, writes in a cross-gender voice.

There is a gentle, seductive rhythm to this work, echoing perhaps the essence of the place she writes about. The writing is precise, yet poetic and, Banyard succeeds brilliantly in capturing the unique quality of the Kootenays and the people who live here.

An enchanting read.

THE BEAUTIFUL MYSTERY

A CHIEF INSPECTOR GAMACHE NOVEL

by Louis Penny

Although I have watched many BBC television productions of murder mysteries, Penny’s book was my first experience of the genre in print. Thankfully, in “The Beautiful Mystery” I seem to have stumbled upon a particularly good example.

Penny follows a formula familiar to me from television: a sensitive, intelligent, yet psychologically wounded chief investigator, Armand Gamache. The personality of Gamache’s sidekick, Jean-Guy, contrasts strongly with his boss’s, but he too is seriously wounded. Both are overseen by an administrator who not only is unhelpful, but perhaps evil.

So far, all these premises must seem pretty familiar to readers of mysteries. What makes Penny’s book stand out is the great attention to detail she gives to her setting. All the action takes place in a remote contemplative monastery in northern Quebec. Here the monks spend most of their time singing and studying Gregorian chants. Penny does a wonderful job painting this world for the reader: the sights, the smells, the textures, but most particularly the sounds, the gorgeous, uplifting, godlike notes and harmonies issuing from the two dozen monks who sing traditional Gregorian chants throughout the day and night.

I have been part of small group which sings such chants myself, so I have an inkling of the power of this seemingly simple (some would say boring) music. But Penny teaches the reader to love the Gregorian chant or, if not to love it, to at least understand why some people would. She also does a wonderful job creating very distinct characters among the monks who, visually, in their black robes and white hoods, look almost identical.

Penny follows a formula familiar to me from television: a sensitive, intelligent, yet psychologically wounded chief investigator, Armand Gamache. The personality of Gamache’s sidekick, Jean-Guy, contrasts strongly with his boss’s, but he too is seriously wounded. Both are overseen by an administrator who not only is unhelpful, but perhaps evil.

So far, all these premises must seem pretty familiar to readers of mysteries. What makes Penny’s book stand out is the great attention to detail she gives to her setting. All the action takes place in a remote contemplative monastery in northern Quebec. Here the monks spend most of their time singing and studying Gregorian chants. Penny does a wonderful job painting this world for the reader: the sights, the smells, the textures, but most particularly the sounds, the gorgeous, uplifting, godlike notes and harmonies issuing from the two dozen monks who sing traditional Gregorian chants throughout the day and night.

I have been part of small group which sings such chants myself, so I have an inkling of the power of this seemingly simple (some would say boring) music. But Penny teaches the reader to love the Gregorian chant or, if not to love it, to at least understand why some people would. She also does a wonderful job creating very distinct characters among the monks who, visually, in their black robes and white hoods, look almost identical.

We learn much about the life of a monk in this book. At no time does Penny suggest these monks are anything more than mere men, yet she is very respectful of their vocation. Her protagonist, Armand, comes to envy them on many levels. It is no small feat to make Catholic monks sympathetic characters in today’s world, and here Penny succeeds spectacularly.

This was a book I was sorry to put down and must confess I will be on the lookout for Book Eight in Chief Inspector Gamache series.

Finally I would like to say that I did not guess the identity of the murderer (I almost never do) but when it was revealed, his motives seemed very logical, and not a bit contrived. I did not feel that important information had been withheld from me, preventing me from making a good guess. For that I thank you, Louise Penny. And for transporting me into a fascinating, colourful and sonorous world.

8/10

This was a book I was sorry to put down and must confess I will be on the lookout for Book Eight in Chief Inspector Gamache series.

Finally I would like to say that I did not guess the identity of the murderer (I almost never do) but when it was revealed, his motives seemed very logical, and not a bit contrived. I did not feel that important information had been withheld from me, preventing me from making a good guess. For that I thank you, Louise Penny. And for transporting me into a fascinating, colourful and sonorous world.

8/10

SEEING and BELIEVING

The Story of the Telescope, or How We Found Our Place in the Universe

by Richard Panek

On first picking up Panek's book, I expected it might be a dry, technical read—even for me, a lifelong amateur astronomer who has some familiarity with telescopes.

But Panek is not interested so much in the telescope as a piece of technology as in how, at certain moments in history, it transformed the way our species saw its place in the universe.

Today we don’t think twice about using scientific instruments to extend our physical senses. In 1609, as Galileo first turned his telescope to the heavens, such an experience was almost unknown. Not only did a telescope make known things--like ships--appear bigger, but it brought into view things which were previously unknown: spots on the sun, mountains on the moon, thousands of never before seen stars in the Milky Way and four moons orbiting Jupiter. Was this just a trick of the instrument? Was the ambitious and disdainful Galileo deceiving them?

But Panek is not interested so much in the telescope as a piece of technology as in how, at certain moments in history, it transformed the way our species saw its place in the universe.

Today we don’t think twice about using scientific instruments to extend our physical senses. In 1609, as Galileo first turned his telescope to the heavens, such an experience was almost unknown. Not only did a telescope make known things--like ships--appear bigger, but it brought into view things which were previously unknown: spots on the sun, mountains on the moon, thousands of never before seen stars in the Milky Way and four moons orbiting Jupiter. Was this just a trick of the instrument? Was the ambitious and disdainful Galileo deceiving them?

It was a huge conceptual leap for the average citizen of the 17th century to make: that the nature of the universe could be unraveled by means other than logic, traditional knowledge and the unaided human senses. Indeed many considered as sacrilege the notion that mere mortals could, by technological means, peer deeply into God’s plan.

Panek relates with flair the contributions of many great astronomers and observers after Galileo with a special emphasis on William Herschel and George Hale whose commitment to building the finest instruments possible did so much to advance astronomy.

A favourite part of the book is when Panek tells of the introduction of photography to astronomy. Suddenly mankind needed no longer to be reliant on individual observers who, being human, could make mistakes, e.g. Percival Lowell’s Martian canals. Instead, photos allowed a permanent record to be made and kept for later, careful study. Still, many astronomers of the time were skeptical. Like stubborn 17th century clerics, many regarded photographic astronomy as a fad; they insisted that any ‘real’ astronomy still needed to be done via an observer looking through a lens. (The notion that mankind is the centre of all things persists throughout the ages.)

Panek’s Seeing and Believing is beautifully written and exquisitely researched. It brought me to a new and deeper appreciation of how humankind has learned to see and the difficult and sometimes painful journey towards believing.

8/10

Panek relates with flair the contributions of many great astronomers and observers after Galileo with a special emphasis on William Herschel and George Hale whose commitment to building the finest instruments possible did so much to advance astronomy.

A favourite part of the book is when Panek tells of the introduction of photography to astronomy. Suddenly mankind needed no longer to be reliant on individual observers who, being human, could make mistakes, e.g. Percival Lowell’s Martian canals. Instead, photos allowed a permanent record to be made and kept for later, careful study. Still, many astronomers of the time were skeptical. Like stubborn 17th century clerics, many regarded photographic astronomy as a fad; they insisted that any ‘real’ astronomy still needed to be done via an observer looking through a lens. (The notion that mankind is the centre of all things persists throughout the ages.)

Panek’s Seeing and Believing is beautifully written and exquisitely researched. It brought me to a new and deeper appreciation of how humankind has learned to see and the difficult and sometimes painful journey towards believing.

8/10

BROTHER ASTRONOMER:

Adventures of a Vatican Scientist

by Guy Consolmagno

Guy Consolmagno is both a Jesuit and an astronomer. To many readers this might seem a strange juxtaposition of occupations, even a contradiction. Consolmagno quickly puts this notion to rest by giving a historical account of the Catholic Church’s lengthy and largely commendable involvement with science. The moon, for example, is littered with craters named after Jesuit astronomers.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Jesuit_scientists

To Brother Guy’s credit, he freely discusses the Church’s notorious episode in “silencing” the great Italian scientist, Galileo. While not justifying the Church’s actions, he does attempt to give a more balanced view of what really happened back in the early 17th century, pointing out how relentlessly Galileo goaded the Church at the time. He talks about how Galileo grew increasingly cantankerous and combative, and showed little willingness to compromise. If the Church authorities over-reacted—which of course they did—Brother Guy points out that, after all, they were only human.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Jesuit_scientists

To Brother Guy’s credit, he freely discusses the Church’s notorious episode in “silencing” the great Italian scientist, Galileo. While not justifying the Church’s actions, he does attempt to give a more balanced view of what really happened back in the early 17th century, pointing out how relentlessly Galileo goaded the Church at the time. He talks about how Galileo grew increasingly cantankerous and combative, and showed little willingness to compromise. If the Church authorities over-reacted—which of course they did—Brother Guy points out that, after all, they were only human.

Mostly the book follows Brother Guy as he goes about doing what astronomers do: writing software to model the interiors of Jovian satellites, struggling to find a technique to measure the density of meteorites without contaminating his samples, or going to Antarctica to collect fresh specimens.

These activities would seem pretty exotic to most of us, but not especially so in the world of astronomers. And in this sense, what is most remarkable about the book, is that Brother Guy comes off as an ordinary ‘guy’, superficially no different than any of his peers. He integrates his faith life seamlessly into his work life. He does not have to make Herculean efforts to keep the two worlds apart. To paraphrase Brother Guy: ‘the truth is the truth; religion and science are looking for the same thing.’ And in another place he says (again I paraphrase): ‘to strive to understand the workings of the Creator is just another way to worship and glorify God.’

Brother Astronomer is written in a homey, casual style, almost as if he were writing a letter to friends. No overall theme dominates the work. It is Brother Guy’s personality that pervades the work: his intelligence and his feelings of inadequacy (apparently even M.I.T. graduates feel such things.) Mostly the scientist-priest comes across as a man who is at peace with the universe at every scale: from the micro to the macro and indeed to the spiritual beyond.

These activities would seem pretty exotic to most of us, but not especially so in the world of astronomers. And in this sense, what is most remarkable about the book, is that Brother Guy comes off as an ordinary ‘guy’, superficially no different than any of his peers. He integrates his faith life seamlessly into his work life. He does not have to make Herculean efforts to keep the two worlds apart. To paraphrase Brother Guy: ‘the truth is the truth; religion and science are looking for the same thing.’ And in another place he says (again I paraphrase): ‘to strive to understand the workings of the Creator is just another way to worship and glorify God.’

Brother Astronomer is written in a homey, casual style, almost as if he were writing a letter to friends. No overall theme dominates the work. It is Brother Guy’s personality that pervades the work: his intelligence and his feelings of inadequacy (apparently even M.I.T. graduates feel such things.) Mostly the scientist-priest comes across as a man who is at peace with the universe at every scale: from the micro to the macro and indeed to the spiritual beyond.

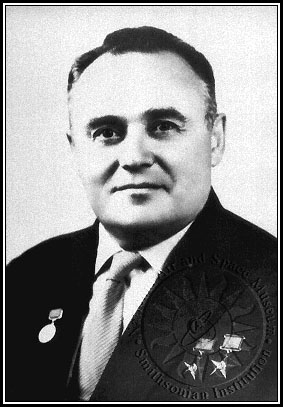

RED MOON RISING

by Matthew Brzezinski

I am a space-junkie. In a general way, I have long been familiar with the events leading up to launch of the world’s first artificial satellite, Sputnik, in 1957. I was particularly familiar with the American part of the story: the public dismay and panic, the rivalry between different branches of the military, and the frustrations of rocket scientists such as Wernher von Braun who felt handcuffed by petty politics. But nowhere in my readings did I have much information about what was happening in Russia at this time.

Red Moon Rising, written by Matthew Brzezinski, addresses this gap in spectacular fashion. In this book, Sergei Korolev, the father of Russian rocket science, the man more than anyone responsible for Sputnik, becomes a fully-fleshed character. The reader becomes entranced by the fortunes of this brilliant but flawed man, sworn to a life of secret anonymity even as his satellites orbit gloriously overhead.

Besides learning about Korolev we learn intimate details about the Russian president, Nikita Khrushchev, and the inner workings of the Soviet Presidium.

Brzezinski does a masterful job portraying the bizarre and sometimes frightening politics occurring in both hemispheres at this time. Most startling to me was to learn of the ultra-provocative policies of President Eisenhower’s Secretary of State at the time, John Foster Dulles. With religious zeal, Dulles did everything he could to demonize the Soviets. He raised the spectre of a surprise attack against the United States when it was clear to everyone in the military that the Soviets had no such capacity. Dulles spoke of “total war” and “massive retaliation” with no seeming purpose but to intimidate the Russians. Dulles regularly ordered bomber missions into Soviet airspace to test their defenses and sent spy planes on reconnaissance missions at an altitude where no Russian jets could respond.

Is it any wonder then that Khrushchev, quite desperately, looked for some means of “retaliation’ of his own?

Of course, Dulles hyper-aggressive, paranoid, anti-Soviet policy came back to bite him big time. For all their supposed ‘intelligence’, the CIA knew nothing about Sergei Korolev and, despite warnings from some quarters that the Soviet Union might soon put a satellite into orbit, no one in the White House believed it. The prevailing opinion was the Russians were little more than backward peasants, led by a bumbling leader and thus incapable of such a technological feat.

Of course they were, and they did. And that story makes up the fascinating content of RED MOON RISING.

8/10

Brzezinski does a masterful job portraying the bizarre and sometimes frightening politics occurring in both hemispheres at this time. Most startling to me was to learn of the ultra-provocative policies of President Eisenhower’s Secretary of State at the time, John Foster Dulles. With religious zeal, Dulles did everything he could to demonize the Soviets. He raised the spectre of a surprise attack against the United States when it was clear to everyone in the military that the Soviets had no such capacity. Dulles spoke of “total war” and “massive retaliation” with no seeming purpose but to intimidate the Russians. Dulles regularly ordered bomber missions into Soviet airspace to test their defenses and sent spy planes on reconnaissance missions at an altitude where no Russian jets could respond.

Is it any wonder then that Khrushchev, quite desperately, looked for some means of “retaliation’ of his own?

Of course, Dulles hyper-aggressive, paranoid, anti-Soviet policy came back to bite him big time. For all their supposed ‘intelligence’, the CIA knew nothing about Sergei Korolev and, despite warnings from some quarters that the Soviet Union might soon put a satellite into orbit, no one in the White House believed it. The prevailing opinion was the Russians were little more than backward peasants, led by a bumbling leader and thus incapable of such a technological feat.

Of course they were, and they did. And that story makes up the fascinating content of RED MOON RISING.

8/10

John Foster Dulles... scary.

GHOST LIGHTS

by Lydia Millet

In Lydia’s Millet’s last novel, How the Dead Dream, we leave the protagonist, T, lost in a jungle in Belize, quite possibly dead. The scene of her new novel starts at a dog kennel, where Susan the secretary of T, has come to retrieve T’s dog, whose owner, everyone has come to fear, may no longer be alive.

With Susan, is her middle-aged husband, Hal. Hal is scarcely mentioned in the previous novel but, in Ghost Lights, he becomes Millet’s protagonist. Once again Millet surprises the reader by choosing an unlikely individual to tell her story: a very ordinary man, almost an everyman, a mere IRS bureaucrat, who yet is complex, fully-fleshed and strangely endearing.

Hal is a flawed man, only too aware of his own mediocrity, married to a woman who is probably too good for him. At the same, Hal has just come to realize that Susan may be unfaithful to him. They have a grown daughter, Casey, who, as a teenager, was badly injured in a car accident and now lives as a paraplegic. Hal, quite illogically, has always felt responsible for the accident, and a sense of mourning, and regret over ‘things that might have been’ has dominated his life since.

Drunk, to a degree he has not know since his youth, Hal declares that he personally will go to the Belize resort where T was last seen, and find Susan’s missing boss. His motives are far from noble. He sees this as an opportunity to escape, if only briefly, the feelings of betrayal, mourning, and ineffectiveness that have become almost too much for him to bear. He cares little for T personally. He will grieve only as far as politeness requires if the man is never found. But Hal shares the story of T with some German tourists who eagerly take it on as their own. With supernatural German efficiency, they organize a search party. Millet’s descriptions of the German couple (Hansel and Gretel—I kid you not) and their two bronze-skinned boys are some of the funniest things I’ve read in a long time. They provide much welcome comic relief in an otherwise melancholy tale.

Millet’s writing always skirts alongside the dark edges of humanity, but never without compassion, often with humour and always with love for her central characters. In How the Dead Dream, the theme of extinction. and the sadness over the final days of things, is central. The theme returns in a surprising way in Ghost Lights, culminating in one of the most memorable death scenes I have ever read.

Definitely worth the read.

8/10

With Susan, is her middle-aged husband, Hal. Hal is scarcely mentioned in the previous novel but, in Ghost Lights, he becomes Millet’s protagonist. Once again Millet surprises the reader by choosing an unlikely individual to tell her story: a very ordinary man, almost an everyman, a mere IRS bureaucrat, who yet is complex, fully-fleshed and strangely endearing.

Hal is a flawed man, only too aware of his own mediocrity, married to a woman who is probably too good for him. At the same, Hal has just come to realize that Susan may be unfaithful to him. They have a grown daughter, Casey, who, as a teenager, was badly injured in a car accident and now lives as a paraplegic. Hal, quite illogically, has always felt responsible for the accident, and a sense of mourning, and regret over ‘things that might have been’ has dominated his life since.

Drunk, to a degree he has not know since his youth, Hal declares that he personally will go to the Belize resort where T was last seen, and find Susan’s missing boss. His motives are far from noble. He sees this as an opportunity to escape, if only briefly, the feelings of betrayal, mourning, and ineffectiveness that have become almost too much for him to bear. He cares little for T personally. He will grieve only as far as politeness requires if the man is never found. But Hal shares the story of T with some German tourists who eagerly take it on as their own. With supernatural German efficiency, they organize a search party. Millet’s descriptions of the German couple (Hansel and Gretel—I kid you not) and their two bronze-skinned boys are some of the funniest things I’ve read in a long time. They provide much welcome comic relief in an otherwise melancholy tale.

Millet’s writing always skirts alongside the dark edges of humanity, but never without compassion, often with humour and always with love for her central characters. In How the Dead Dream, the theme of extinction. and the sadness over the final days of things, is central. The theme returns in a surprising way in Ghost Lights, culminating in one of the most memorable death scenes I have ever read.

Definitely worth the read.

8/10

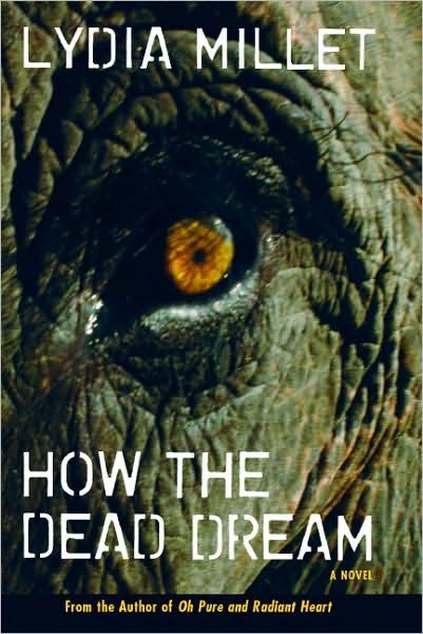

HOW THE DEAD DREAM

by Lydia Millet

Before reading this book, I had no idea who this author was. Yet, within a dozen pages, I was coming to understand that I was reading something quite special. The fact that I should be so impressed by Millet’s writing is all the more amazing when I reflect that the protagonist of the book is a devoted capitalist—hardly a person I would normally be drawn to. Throughout most of the book, he is simply referred to as ‘T’. Yet T’s transformation is both poetic and spectacular.

As a boy T’s principle passion is to ‘collect’ money and stash it under his pillow at night. He receives a visceral thrill as he studies the lithographic etching on the American dollar bill. In college, he is a friend to all, but intimate with no one. It is ‘T’ who is the designated driver, ‘T’ who sorts out his friend’s indiscretions and messy relationships. ‘T’ himself avoids all youth’s usual excesses, in favour of focusing on the market, real estate and mapping out his destiny. He is enamoured with a vision of high rises, new highways, bright lights, holiday resorts, retirement homes in the desert, the creation of which will become the source of his material wealth and self-worth.

It is worth noting that the protagonist of “How the Dead Dream” is a male, and the writer female. It is the most convincing cross-gender writing I have ever come across. Never once did I doubt the authenticity of the male voice of ‘T’.

But what makes this novel so good? The writing to be sure, which is extremely lyrical at times, and the psychological insights Millet has which are quite breath-taking. In the end, what is most impressive, is the journey she takes the reader on. We meet ‘T’ arch-capitalist, without a soul it seems, at first, but then gradually we see a change take place. It begins when he is driving at night and hits a coyote. He stops his car to check on it. It’s not yet dead. He feels obligated to carry it off road—even though he doesn’t know what to expect—after all, it might bite him. He stays with it until it takes its last breath. That moment changes him, though he doesn’t realize it at the time.

Later ‘T’ who, till this time, has never surrendered himself to anyone emotionally meets Beth, the love of his life, but tragedy strikes, and that relationships lasts only a short time. His father, a man in his sixties, suddenly, and without explanation, leaves his wife. ‘T’ does his best to console his mother, and has her live with him. She develops early dementia. The scenes of ‘T’, the son, speaking with a mother who doesn’t even recognize him, in fact thinks he is a criminal, are heart-wrenching.

Quite unexpectedly—to me, at least—‘T’ then develops an obsession with endangered animals, going to great lengths to be in their company. For him, they come to represent the world condition, the ultimate fate of each individual and each species, creatures near their end and alone, desperately alone. Some of the novel’s most memorable moments take place as ‘T’ stands eye-to-eye with some of these forlorn and mighty creatures.

This might help explain the otherwise quite obscure cover of the book: it is a close up of an elephant’s eye.

I did not read Millet’s book in one sitting—I never do, but I could very easily imagine myself making an exception for this book. It is that compelling, that beautifully written, that filled with compassion, longing and even humour. It’s one of the best things I’ve read in years.

9/10.

Only the “classics of literature would get a higher rating from me. I have a new favourite author!

As a boy T’s principle passion is to ‘collect’ money and stash it under his pillow at night. He receives a visceral thrill as he studies the lithographic etching on the American dollar bill. In college, he is a friend to all, but intimate with no one. It is ‘T’ who is the designated driver, ‘T’ who sorts out his friend’s indiscretions and messy relationships. ‘T’ himself avoids all youth’s usual excesses, in favour of focusing on the market, real estate and mapping out his destiny. He is enamoured with a vision of high rises, new highways, bright lights, holiday resorts, retirement homes in the desert, the creation of which will become the source of his material wealth and self-worth.

It is worth noting that the protagonist of “How the Dead Dream” is a male, and the writer female. It is the most convincing cross-gender writing I have ever come across. Never once did I doubt the authenticity of the male voice of ‘T’.

But what makes this novel so good? The writing to be sure, which is extremely lyrical at times, and the psychological insights Millet has which are quite breath-taking. In the end, what is most impressive, is the journey she takes the reader on. We meet ‘T’ arch-capitalist, without a soul it seems, at first, but then gradually we see a change take place. It begins when he is driving at night and hits a coyote. He stops his car to check on it. It’s not yet dead. He feels obligated to carry it off road—even though he doesn’t know what to expect—after all, it might bite him. He stays with it until it takes its last breath. That moment changes him, though he doesn’t realize it at the time.

Later ‘T’ who, till this time, has never surrendered himself to anyone emotionally meets Beth, the love of his life, but tragedy strikes, and that relationships lasts only a short time. His father, a man in his sixties, suddenly, and without explanation, leaves his wife. ‘T’ does his best to console his mother, and has her live with him. She develops early dementia. The scenes of ‘T’, the son, speaking with a mother who doesn’t even recognize him, in fact thinks he is a criminal, are heart-wrenching.

Quite unexpectedly—to me, at least—‘T’ then develops an obsession with endangered animals, going to great lengths to be in their company. For him, they come to represent the world condition, the ultimate fate of each individual and each species, creatures near their end and alone, desperately alone. Some of the novel’s most memorable moments take place as ‘T’ stands eye-to-eye with some of these forlorn and mighty creatures.

This might help explain the otherwise quite obscure cover of the book: it is a close up of an elephant’s eye.

I did not read Millet’s book in one sitting—I never do, but I could very easily imagine myself making an exception for this book. It is that compelling, that beautifully written, that filled with compassion, longing and even humour. It’s one of the best things I’ve read in years.

9/10.

Only the “classics of literature would get a higher rating from me. I have a new favourite author!

THE DANGEROUS ANIMALS CLUB

by Stephen Tobolowsky

This book was given to me by my daughter and fiancé who are both actors working out of Toronto. Knowing my own modest background in theatre, they thought I might find it a good read and I did. But not exactly for the expected reasons.

As advertised, Tobolowsky (Tobo) gives us a quirky account of his rise to the status of one of Hollywood’s most successful (yet anonymous) character actors. Tobo has appeared in numerous movies and television series. I remember him best for his appearances in Glee and Heroes. I was reassured to read that, as an actor, he was just as mystified by the plot of Heroes as I was, as a viewer.

Tobo begins his book by recalling his boyhood in Oak Cliff, Texas. There, he and a friend make it their mission to scour the neighbourhood in hope of capturing and bringing home the most dangerous animals they can find. It’s a funny story, but maybe a little misleading as the title of the book.

Most of the book follows Tobo’s long and meandering struggle to make it as a professional actor. Some of the anecdotes he tells are very amusing, such as when he is performing for a Santa Monica theatre company for children. This is Tobo’s first professional gig and he has had to memorize his lines phonetically since he doesn’t know Spanish. The moment of truth arrives; he is supposed to say, Pasa, jovincita (“Come in, little girl”). Instead he blurts out, Peto, jovincita which means “Fart, little girl.” This brings the down the house as such mistakes are apt to do with an audience of eight-year-olds. He is fired after the performance.

But Stephen Tobolowsky is nothing, if not resilient.. Despite many setbacks and many disappointments, he maintains his sense of humour, his sense of optimism and, ultimately—and this is what I like best—his sense of gratitude.

At one point in his life, Stephen has a bad accident and breaks his neck. For nine months he is in a brace and is effectively removed from the world of auditions. Somehow, near the end of this period, his agent lands him an audition for a role in Heroes. He arrives at the building where auditions are supposed to take place, still wearing his brace. He’s afraid to take it off. After such a long time out of the loop, he’s nervous about the whole processing of auditioning.

When Tobo finally is let into the building he finds it virtually deserted. No one is expecting him. It turns out the auditions are the next day… One could easily imagine an actor throwing a hissy-fit at such a point. But Tobo just takes breath, reminds himself how lucky he is to even be in the acting industry and drives placidly back home. Next day he returns like nothing has happened, and he gets the part.

It is such incidents as this that really make the book for me: moments when we come to appreciate Stephen’s humanity, his good heart, his openness to new possibilities.

Tobo did indeed teach me many new and interesting things about the acting industry. For example, I learned the difference between stage acting, which I understand, and movie acting which I do not. It helped explain why I wasn’t hired, even as an extra, the one time I auditioned for a movie!

Many times I laughed out loud while reading this book: once, for example at learning his mother’s advice as Tobo rents his first apartment in L.A. “Stephen, whatever you do, don’t go into porno.” But I also sighed too, in sharing Stephen’s disappointments and regrets. By the end of the book, I am left feeling I know far more than a bunch of funny stories. I have come to know the man, Stephen Tobolowsky, and he’s someone I like and someone I wish well.

Here’s what he writes to start of his acknowledgements at the end of the book: “To my wife, Ann, for the countless hours, the love, the crises weathered at every stage of our lives together—including this book.”

What’s not to like?

A very solid, 7/10.

WARPWORLD

by Kristene Perron & Joshua Simpson

Warp World is a sci-fi thriller written by Kristene Perron and Joshua Simpson. And “thriller” is a key word in describing this work. The pacing is excellent. In this book of almost 500 pages, there is never a dull moment. Seg and Ama, Warpworld’s two protagonists, are very finely drawn, yet different enough to ensure a constant tension and electricity between them. Much attention is given to the book’s secondary characters. My favourite is Jarin, the Charles Laughton-Roman patrician-type mentor of Seg—the consummate politician, patiently working to change a world which doesn’t even realize it’s in decline.

The authors of Warp World have paid tremendous attention to detail. The technology of weapons and transportation, anatomical details of the inhabitants, their anthropological histories, their mythologies—all these have been thought out in detail and make the reader’s experience of two alien worlds both sensual and convincing.

Warp World falls into a genre of literature I don’t generally read. Thanks to Perron and Simpson’s fine writing however, I may have to reconsider.

The authors of Warp World have paid tremendous attention to detail. The technology of weapons and transportation, anatomical details of the inhabitants, their anthropological histories, their mythologies—all these have been thought out in detail and make the reader’s experience of two alien worlds both sensual and convincing.

Warp World falls into a genre of literature I don’t generally read. Thanks to Perron and Simpson’s fine writing however, I may have to reconsider.