Nascent Poet or Hotheaded Murderer?

by Sean Arthur Joyce

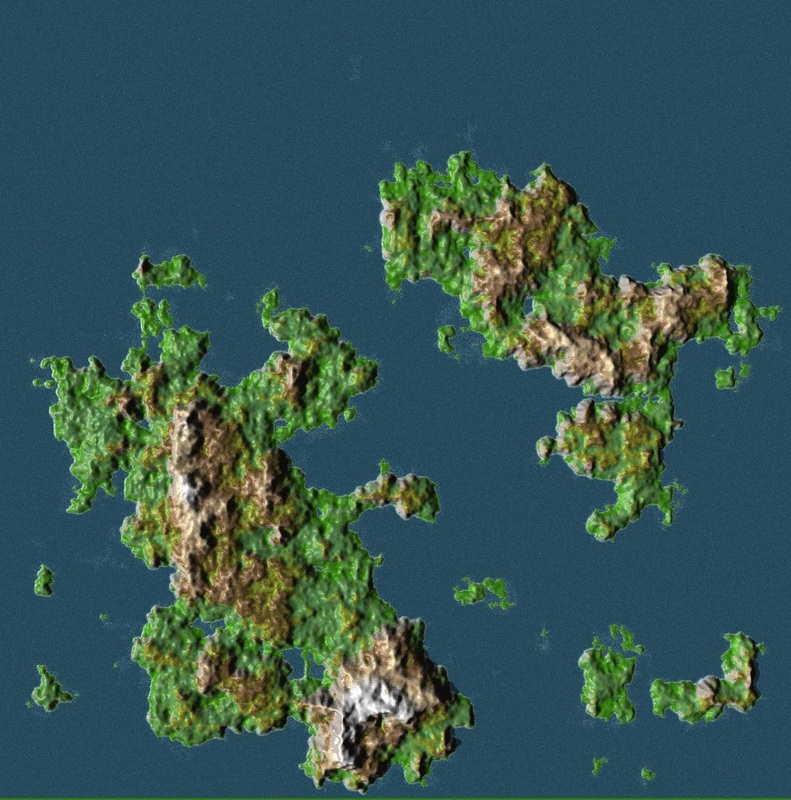

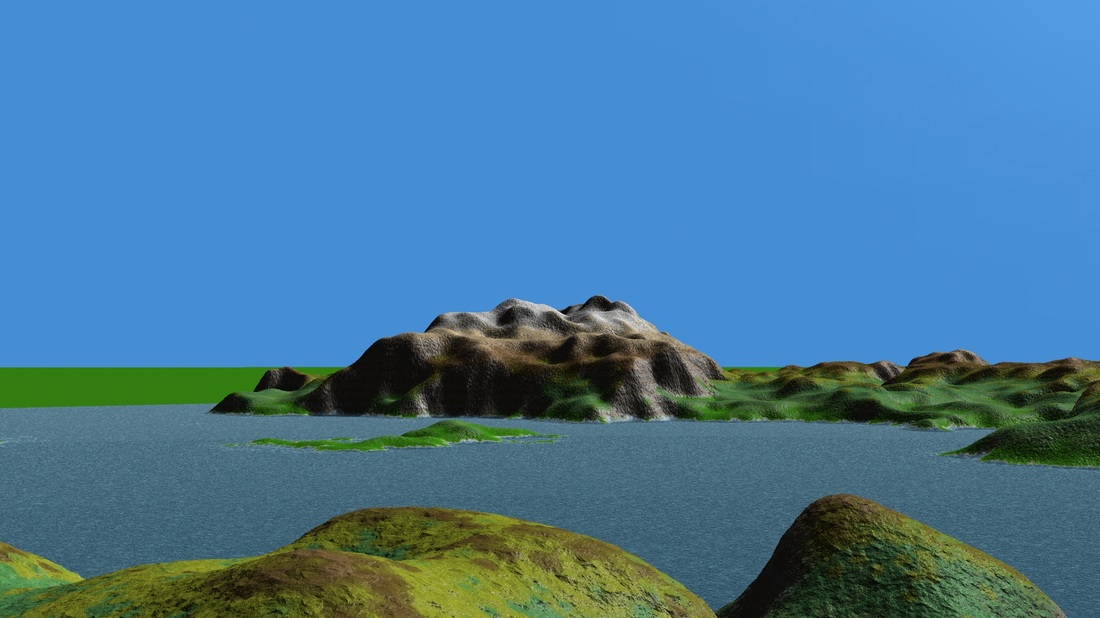

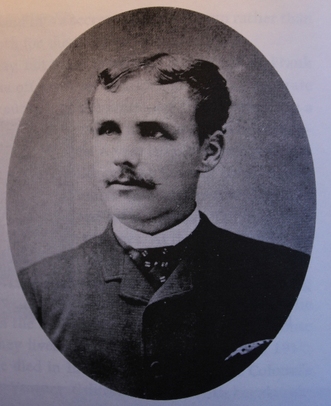

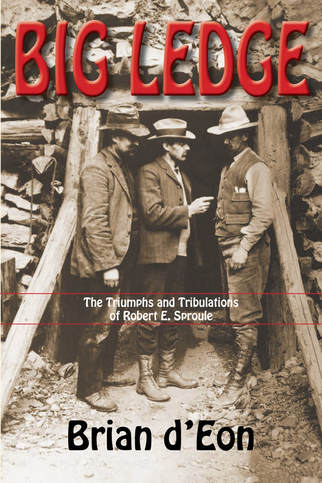

Big Ledge by Brian D’Eon is that rarity in historical fiction—a story that combines historical veracity with narrative fluency and a deep poetic sensibility. D’Eon starts the tale from its endpoint, with its protagonist Robert Sproule sitting in a jail cell telling his story to a priest on the eve of his execution in 1886. Sproule is well-known to readers of Kootenay history for having been convicted of the murder of Thomas Hamill, with whom he had a dispute over ownership of the Bluebell mining claim on the east shore of Kootenay Lake.

The author captures well the colloquialisms of late 19th century speech, adding to the tale’s believability. As any skilled writer knows, dialogue is a prime vehicle for storytelling, not just for revealing plot points but quirks of speech and character. D’Eon effortlessly masters the technique, easily drawing us into the tale. He also appreciates the value of including other sensory information in the narrative. Sproule’s confession to the priest is laced with his memories of the “pristine” Kootenay country—not just its visual grandeur but its smells: “…the firs and cedar, the black earth, the wild strawberries, even the smell of the lake—each has its own smell you know—that’s how salmon know where they’re going.”

The poetic dimension enters with a secondary set of characters, the Archangel Michael and Hindu goddess Parvati, heavenly eavesdroppers whose wry asides add a funny, philosophical dimension. Poetic quotes from Blake, Shakespeare, the Bible and others are woven seamlessly throughout Sproule’s narrative, though it’s uncertain what level of education he possessed, or whether he would have had quite the broad vocabulary D’Eon imagines. The dialogue between Archangel Michael and Parvati is often laced with humour, as when Michael wonders what it is that attracts mortals to tobacco. “Ah,” Parvati answered, happy to explain: “A native custom, and a most clever means of revenge against European invaders.” The celestial pair function as a kind of Greek chorus, commenting from the wings as they debate whether Sproule is an unjustly accused prospector with a poetic nature or simply a hotheaded murderer. In so doing, D’Eon skillfully engages one of Canadian history’s great mysteries, one that—given the contradictory historical accounts—may never be solved.

Adding to this narrative of multiple perspectives is C.J. Woodbury, a reporter who wrote several accounts of the Sproule-Hamill trial. Speaking to his fiancée Kate Buchanan, Woodbury makes an observation that could serve as the book’s basic premise: “It was striking the way people could so quickly judge these things. As if there could be no doubt about the matter. Label someone and you no longer had to think about him as a person.” With explorations of Woodbury as well as William Baillie-Grohman, D’Eon sidesteps the trap of investing too heavily in his protagonist’s point of view.

D’Eon successfully applies the techniques of the novelist to flesh out what would otherwise be—at best, given what we know of Sproule and Hamill—a very short story. One of the writer’s primary tools is a sense of empathy for a story’s characters, even those with an unsavoury nature. D’Eon clearly identifies strongly with the version of Sproule he has created, and his characterization is highly appealing. For many readers, it will raise serious questions about Sproule’s guilt and the “justice” meted out to him.

You can almost smell the smoke of a miner’s campfire, curling up into a night sky not yet crowded with satellites and air pollution, lake waters lapping meditatively as the tale unwinds. D’Eon has written a historical novel that ranks with the best of them.