Sandra Hartline

|

There’s romance, mystery and prophecy on the sandstone island of Uluru, an isolated rock formation in central Australia which is sacred to the aboriginal people of the area. James Cook is twenty-nine, part aboriginal and senior advisor to the Minister for Parks and Aboriginal Affairs, Patrick Mahoney. “We've got a problem up at Ayer's Rock,” Mahoney tells him. “They want the Rock back. The Aboriginals say it belongs to them, and they want us to clear out.” The Minister sends James to investigate, and James becomes enamoured of Pamela, a comely anthropologist who can also serve as interpreter. Pam introduces him to Billy, an aboriginal elder, who predicts there is something unusual about to happen in the sky. It’s the star Eta Carinae, bright and beautiful, possibly about to explode. Does its nearness herald global warming, a catastrophe, or something else altogether? This entertaining tale blends astronomy and oral history and suggests some surprising conclusions.

Sandra Hartline

0 Comments

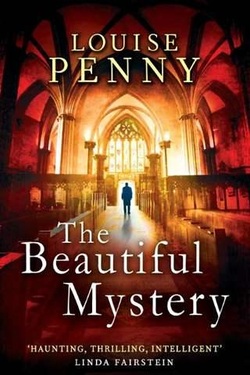

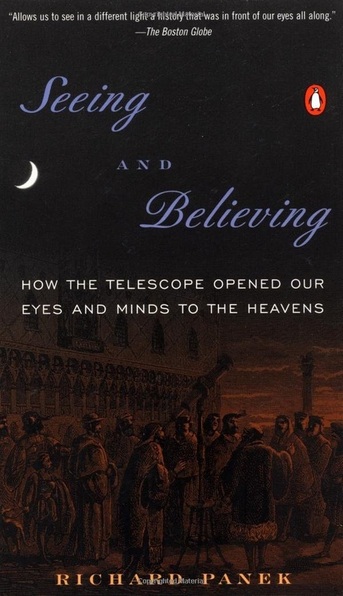

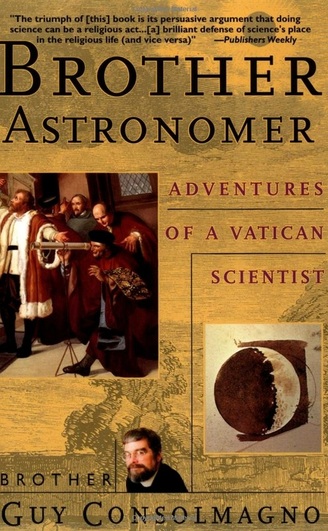

Although I have watched many BBC television productions of murder mysteries, Penny’s book was my first experience of the genre in print. Thankfully, in “The Beautiful Mystery” I seem to have stumbled upon a particularly good example. Penny follows a formula familiar to me from television: a sensitive, intelligent, yet psychologically wounded chief investigator, Armand Gamache. The personality of Gamache’s sidekick, Jean-Guy, contrasts strongly with his boss’s, but he too is seriously wounded. Both are overseen by an administrator who not only is unhelpful, but perhaps evil. So far, all these premises must seem pretty familiar to readers of mysteries. What makes Penny’s book stand out is the great attention to detail she gives to her setting. All the action takes place in a remote contemplative monastery in northern Quebec. Here the monks spend most of their time singing and studying Gregorian chants. Penny does a wonderful job painting this world for the reader: the sights, the smells, the textures, but most particularly the sounds, the gorgeous, uplifting, godlike notes and harmonies issuing from the two dozen monks who sing traditional Gregorian chants throughout the day and night. I have been part of small group which sings such chants myself, so I have an inkling of the power of this seemingly simple (some would say boring) music. But Penny teaches the reader to love the Gregorian chant or, if not to love it, to at least understand why some people would. She also does a wonderful job creating very distinct characters among the monks who, visually, in their black robes and white hoods, look almost identical.  We learn much about the life of a monk in this book. At no time does Penny suggest these monks are anything more than mere men, yet she is very respectful of their vocation. Her protagonist, Armand, comes to envy them on many levels. It is no small feat to make Catholic monks sympathetic characters in today’s world, and here Penny succeeds spectacularly. This was a book I was sorry to put down and must confess I will be on the lookout for Book Eight in Chief Inspector Gamache series. Finally I would like to say that I did not guess the identity of the murderer (I almost never do) but when it was revealed, his motives seemed very logical, and not a bit contrived. I did not feel that important information had been withheld from me, preventing me from making a good guess. For that I thank you, Louise Penny. And for transporting me into a fascinating, colourful and sonorous world. 8/10  On first picking up Richard Panek's book, I expected it might be a dry, technical read—even for me, a lifelong amateur astronomer who has some familiarity with telescopes. But Panek is interested not so much in the telescope as a piece of technology as in how, at certain moments in history, it has transformed the way our species saw its place in the universe. Today we don’t think twice about using scientific instruments to extend our physical senses. In 1609, as Galileo first turned his telescope to the heavens, such an experience was almost unknown. Not only did a telescope make known things--like ships--appear bigger, but it brought into view things which were previously unknown: spots on the sun, mountains on the moon, thousands of never before seen stars in the Milky Way and four moons orbiting Jupiter. Was this just a trick of the instrument? Was the ambitious and disdainful Galileo deceiving them?  It was a huge conceptual leap for the average citizen of the 17th century to make: that the nature of the universe could be unraveled by means other than logic, traditional knowledge and the unaided human senses. Indeed many considered as sacrilege the notion that mere mortals could, by technological means, peer deeply into God’s plan. Panek relates with flair the contributions of many great astronomers and observers after Galileo with a special emphasis on William Herschel and George Hale whose commitment to building the finest instruments possible did so much to advance astronomy. A favourite part of the book is when Panek tells of the introduction of photography to astronomy. Suddenly mankind needed no longer to be reliant on individual observers who, being human, could make mistakes, e.g. Percival Lowell’s Martian canals. Instead, photos allowed a permanent record to be made and kept for later, careful study. Still, many astronomers of the time were skeptical. Like stubborn 17th century clerics, many regarded photographic astronomy as a fad; they insisted that any ‘real’ astronomy still needed to be done via an observer looking through a lens. (The notion that mankind is the centre of all things persists throughout the ages.) Panek’s Seeing and Believing is beautifully written and exquisitely researched. It brought me to a new and deeper appreciation of how humankind has learned to see and the difficult and sometimes painful journey towards believing. 8/10 Ode to a Dandelion (an original poem, written this very day, by a normally prosaic novelist) O yellow dandel’in, good faithful friend o’ mine, Persistent, exuberant weed; You have taken first place in biology's race, Thanks to your billowy seed.  It occurred to me today, as I walked through the streets of Nelson, looking at the riot of spring before my eyes, how much psychic energy people waste worrying about weeds. About dandelions in particular. “Noxious” weeds some would call them. An unwarranted charge to be sure. Their young greens are excellent in salad and you can make wine from the plant. All for free. What more could a person ask for? No preparation necessary. No need to fertilize or add nitrogen to the soil or lime or God knows what exotic combination of rare metals to make them bloom. They just bloom on their own. In spite of us. Imagine: an organism that does not seem to depend on our goodwill. Now, if that is not heroic, I don’t know what is.  Some people, I am told, actually grow depressed at the sight of a green lawn full of dandelions or, worse still, psychotic, quickly gathering all manner of poisons and Gothic metal implements to rip apart the innocent plant. But why? Their yellow heads are a free gift, each a miniature sun, exuberant, cheerful, ready to fill one’s heart with cheer and goodwill. And a lawn full of them--simply the cheer magnified. Imagine a field full of poppies (we have written poems about such things) or wild roses, or lilies, or bluebells. Is there something especially offensive about the yellowness?  No, I say. We have moved past racism, past sexism, past most ‘isms’ in fact. Let us not forget ‘weedism.’ Dandelions are wonderful: the starlings of the flora universe, heroic colonists of almost every habitat known to man, growing all season long, a hymn to photosynthesis and the evolution of species. Long live the dandelion! (not that they need my goodwill—they are like cats in that way, and therefore deserve respect.)  Guy Consolmagno is both a Jesuit and an astronomer. To many readers this might seem a strange juxtaposition of occupations, even a contradiction. Consolmagno quickly puts this notion to rest by giving a historical account of the Catholic Church’s lengthy and largely commendable involvement with science. The moon, for example, is littered with craters named after Jesuit astronomers. To Brother Guy’s credit, he freely discusses the Church’s notorious episode in “silencing” the great Italian scientist, Galileo. While not justifying the Church’s actions, he does attempt to give a more balanced view of what really happened back in the early 17th century, pointing out how relentlessly Galileo goaded the Church at the time. He talks about how Galileo grew increasingly cantankerous and combative, and showed little willingness to compromise. If the Church authorities over-reacted—which of course they did—Brother Guy points out that, after all, they were only human.  Mostly the book follows Brother Guy as he goes about doing what astronomers do: writing software to model the interiors of Jovian satellites, struggling to find a technique to measure the density of meteorites without contaminating his samples, or going to Antarctica to collect fresh specimens. These activities would seem pretty exotic to most of us, but not especially so in the world of astronomers. And in this sense, what is most remarkable about the book, is that Brother Guy comes off as an ordinary ‘guy’, superficially no different than any of his peers. He integrates his faith life seamlessly into his work life. He does not have to make Herculean efforts to keep the two worlds apart. To paraphrase Brother Guy: ‘the truth is the truth; religion and science are looking for the same thing.’ And in another place he says (again I paraphrase): ‘to strive to understand the workings of the Creator is just another way to worship and glorify God.’ Brother Astronomer is written in a homey, casual style, almost as if he were writing a letter to friends. No overall theme dominates the work. It is Brother Guy’s personality that pervades the work: his intelligence and his feelings of inadequacy (apparently even M.I.T. graduates feel such things.) Mostly the scientist-priest comes across as a man who is at peace with the universe at every scale: from the micro to the macro and indeed to the spiritual beyond. |

Brian d'Eon, fiction writer: whose work modulates between speculative, historical and magical realism. Categories

All

|