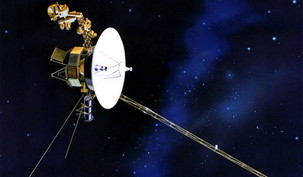

This idea is simply wrong, they argue. They point to the fact that there have been many scientific revolutions in physics since the time of Newton, yet none of them have proved Newton to be "wrong". Newton's ideas are not wrong so much as "limited". To the present day, it is still Newton's equations that successfully guide spacecraft to the planets. What is true is that insights by Einstein and others have shown that Newton's equations are not sufficient to explain how the universe works in all circumstances e.g. for objects traveling near the speed of light. But Einstein's theories do not overthrow Newton's, they encompass them. "Science does not simply toss one theory out for another: it makes real progress toward even-larger truths." (26)

The problem many modern people have in accepting that a true universal cosmology is possible may owes its origins to a very un-modern aesthetic that still lingers in people's minds. John Keats summarizes this viewpoint nicely in his "Ode to a Grecian Urn" when he says, "Beauty is truth, truth beauty--that is all/ ye know on earth, and all ye need to know."

A lovely sentiment, but very unproductive when trying to understand the world of quantum physics. In fact, maybe Keats is blameless because he does states that truth and beauty are equivalent on earth. If we restrict this sentiment to things experienced on earth, then we are safe enough.

As Primack and Abrams point out. "The universe is under no obligation to be the way our aesthetic sensibilities might wish or expect."(29)

No less an intellectual giant than Albert Einstein fell prey to this faulty thinking when objecting to quantum theory because he couldn't believe God would play dice. Clearly the idea offended his sense of order and beauty.

Intuition and common sense are valuable assets in the human tool box, so long as we apply them to terrestrial experiences. But, warn Primack and Abrams, "When we extrapolate such feelings about how things work to the universe, what we are actually imagining is how the universe would work in miniature if it existed on the size scale of our experience. But miniatures never work like the real thing." (31) This is one of the great central ideas of the book. The size scale of things is fundamental in understanding how they work. You cannot, for example, increase an ant up to the size of an elephant and expect it to work, nor do the reverse.