But Panek is interested not so much in the telescope as a piece of technology as in how, at certain moments in history, it has transformed the way our species saw its place in the universe.

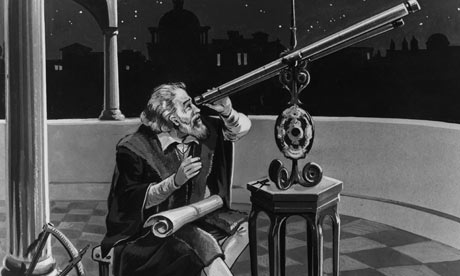

Today we don’t think twice about using scientific instruments to extend our physical senses. In 1609, as Galileo first turned his telescope to the heavens, such an experience was almost unknown. Not only did a telescope make known things--like ships--appear bigger, but it brought into view things which were previously unknown: spots on the sun, mountains on the moon, thousands of never before seen stars in the Milky Way and four moons orbiting Jupiter. Was this just a trick of the instrument? Was the ambitious and disdainful Galileo deceiving them?

Panek relates with flair the contributions of many great astronomers and observers after Galileo with a special emphasis on William Herschel and George Hale whose commitment to building the finest instruments possible did so much to advance astronomy.

A favourite part of the book is when Panek tells of the introduction of photography to astronomy. Suddenly mankind needed no longer to be reliant on individual observers who, being human, could make mistakes, e.g. Percival Lowell’s Martian canals. Instead, photos allowed a permanent record to be made and kept for later, careful study. Still, many astronomers of the time were skeptical. Like stubborn 17th century clerics, many regarded photographic astronomy as a fad; they insisted that any ‘real’ astronomy still needed to be done via an observer looking through a lens. (The notion that mankind is the centre of all things persists throughout the ages.)

Panek’s Seeing and Believing is beautifully written and exquisitely researched. It brought me to a new and deeper appreciation of how humankind has learned to see and the difficult and sometimes painful journey towards believing.

8/10