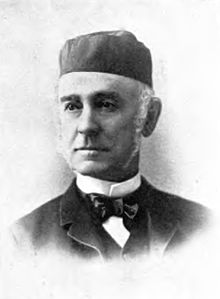

For some, his crowning achievement would be his becoming California's first Mason grand master.

Ainsworth began his working life on steamboats in the Mississippi and became a river master by age twenty-five. Unlike most young men of his generation, Ainsworth traveled out West not to make his money panning for gold, but to provide the transportation and supplies that would be desperately needed by his starry-eyed peers.

Ainsworth was a rich man by the time the California gold rush was over; most of the prospectors weren’t. He went on to repeat the pattern in British Columbia, using his steamer to ferry men up the Fraser River.

Successful as he was with his steamers, by the 1870’s, Ainsworth quickly realized that railways would soon displace them, and began seeking other schemes to increase his wealth.

When word leaked out about mineral riches in the Kootenays, Ainsworth wasted no time.

Wily as always, Ainsworth understood that both Ottawa and Victoria were scared witless by the prospect of the wealth of the Kootenays being sucked southward. The Northern Pacific railroad almost touched the Canadian border. From there it was a short hop to Kootenay Lake and all its mineral riches. Very little infrastructure would be required to haul the ore out to American smelters.

So Ainsworth presented himself to the authorities in Victoria as something of a saviour. He proposed building a spur line railway—at his own cost—all within the Canadian border. It would run from what we now call Arrow Lake to Kootenay Lake, not far from present day Balfour. This would allow the minerals to be transported the short distance from Big Ledge to the spur line and then, by another of Ainsworth's ferries, up to the Columbia River. There it would meet the CPR (whose completion was still three years in the future) and finally safely to a Canadian smelter.

All Ainsworth asked for in exchange for his investment was a deed to all property on either side of Kootenay Lake and its tributaries to a distance of six miles from the shore! A huge tract of land! And had the government in British Columbia agreed to it, it would have finalized one of the greatest land grabs in Canadian history.

Before long, saner voices rose in protest, making it clear to Victoria what a bad deal this actually was. Along with these cautionary tales came a proposal from an English entrepreneur, Baillie-Grohman, who proposed putting a steamer onto Kootenay Lake and transforming the flooded lands south of the lake into lucrative farm land.

For a while, Victoria hemmed and hawed, thinking perhaps they might find a way to have their cake and eat it too. Eventually, however, they turned down the Ainsworth proposal and John C. had to content himself with whatever profits he could make off activity at the Big Ledge mine site. Even this notion soon became problematic. By 1886 Ainsworth decided not renew any of his mining interests at Big Ledge, leaving its development entirely in the hands of Hendryx and the Kootenay Lake Mining & Smelting Company.